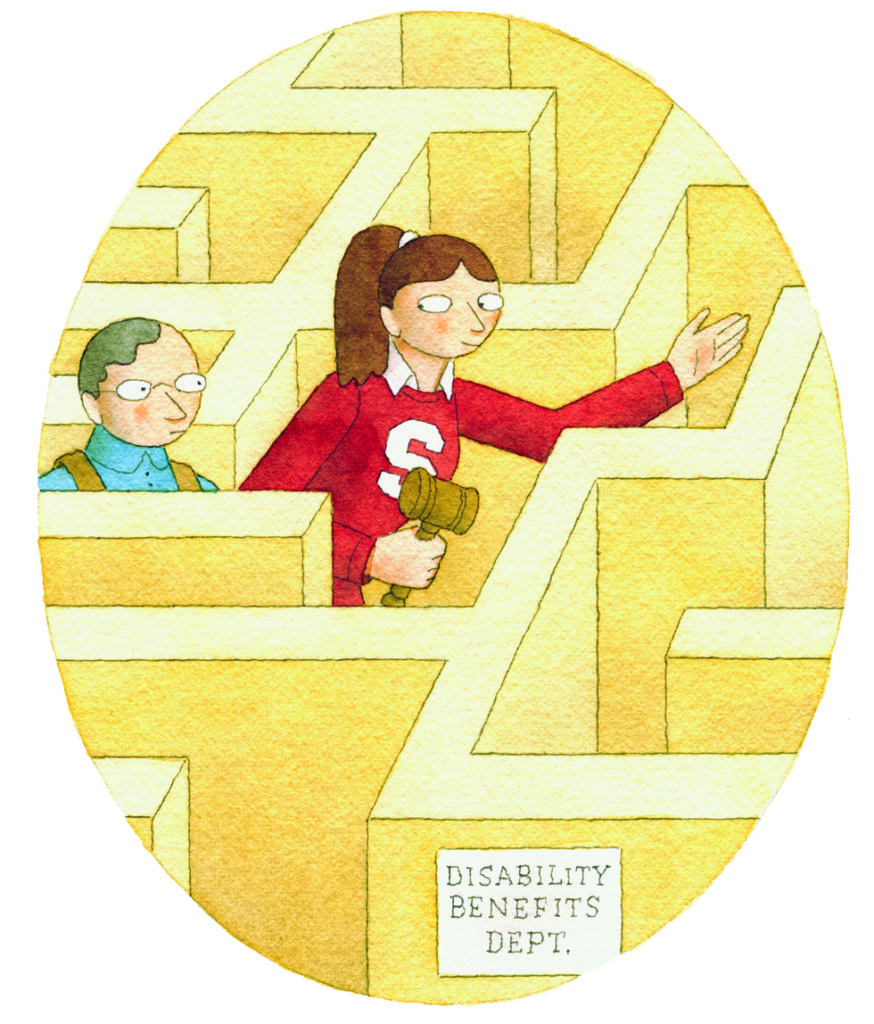

Students Help Clients Navigate the Social Security Maze

Because of an injury-related disability, “Ed” can’t do many of the things he used to do—like fix cars, walk more than a block, or stand in the DMV line. He has spent many nights shuttling between his truck and shelters, looking for a place to sleep. He has waited months to be seen at the public orthopedics clinic.

Jessica Dragonetti, JD ’15, met Ed in her first year at Stanford Law School when she participated in the law school’s Social Security Disability Pro Bono Project (SSDP). As an advanced Community Law Clinic student, Dragonetti recently represented Ed at a hearing. Armed with new medical evidence of her client’s physical impairments, she presented testimony, cross-examined experts, and won a bench decision granting him on-going and retroactive benefits. Dragonetti’s experience, starting as a volunteer in the SLS pro bono program and going on to provide full-scale representation as a clinic student, exemplifies the arc of experiential education now available at Stanford Law.

“This money has changed Ed’s life,” says Dragonetti. “He has used back benefits to repair his truck, and the steady, monthly disability income is enabling him to provide for himself and finally qualify for affordable housing. Social Security disability benefits won’t solve everything, but they’re a start.”

Ed is just one of hundreds of individuals in the greater Palo Alto area who are in desperate need of disability benefits, but who lack the resources to get them. Two closely intertwined SLS programs, the SSDP and the Community Law Clinic (CLC), provide scores of SLS students each year the opportunity to help such clients apply, get hearings, and appeal decisions so that they may receive the benefits they deserve. Volunteers, most of them 1Ls, meet with clients in the community to work with them on the initial stages of applying for disability.

Students in the CLC, one of Stanford Law’s 11 clinics, pick up the cases in their later stages, representing clients whose applications were denied in hearings before federal administrative law judges, and in appeals.

“The Social Security disability regulations are so complicated that even first-year law students come to me practically in tears trying to figure them out,” says Lisa Douglass, lecturer in law and supervising attorney in the CLC. Douglass directs both the SSDP and the clinic’s Social Security disability practice. “For people who have the kinds of mental or physical limitations that our clients do, the process is completely insurmountable. Helping someone navigate this process is a great education in the actual functioning of the federal administrative state and in how our legal systems operate on the ground.”

George Warner, JD ’17, is one of 14 students presently serving in the SSDP who meet with clients once a week at a Palo Alto homeless center, the Opportunity Center of the Midpeninsula. First, he elicits from them information about how their disabilities are preventing them from working. He then translates the information into the claims forms, supplementing it with documentation he must obtain from health care providers.

“A lot of our clients haven’t had adequate medical care for their conditions, which can make obtaining objective documentation of those conditions challenging,” says Warner, who became interested in social justice issues while working as a news editor for the Huffington Post prior to coming to Stanford.

Filling out applications is just one step in a rigorous process. The federal program has such stringent requirements of proof that a disability prevents a person from working that, nationwide, roughly two-thirds of applications are declined the first time. Although SSDP has had more success, follow-up steps are frequently needed. The Community Law Clinic picks up where SSDP leaves off, providing second- and third-year law students with the opportunity to represent clients in hearings and appeals.

The SSDP was started in 2007, when the Opportunity Center in Palo Alto approached the law school for help for its clientele on disability benefits. The program, which initially served 5 clients, now has 80 ongoing cases, with 30 more in the CLC.

“SSDP has made an immeasurable difference in the lives of many of our clients over the past eight years,” says Philip Dah, program director for InnVision Shelter Network, which runs the case management services at the Opportunity Center. “The stable income the law students help our clients secure has enabled us to place many people in permanent housing.” However, “there’s still an endless stream of people needing help,” says Douglass.

The project and clinic are not only transforming the lives of clients, but also enriching the experience of Stanford Law students. “The SSDP to CLC partnership is a great example of the innovative experiential education program we have built at Stanford,” says Juliet Brodie, associate dean of clinical education and director of the CLC. “The two programs enable us to serve a lot of very needy clients in the communities that surround the law school and to expose law students to a wide range of concrete lawyering competencies—from client interviewing to fact investigation to written and oral advocacy.”

“As a 1L in SSDP you get a lot of training but also a lot of responsibility early on. That combination excites me,” says Warner. “Working with clients who have sensitive issues also helps me develop an important aspect of lawyering that you can’t learn from doctrinal work—good communication skills.”

“Learning how to represent clients at hearings has been phenomenal,” says Dragonetti. Having segued from SSDP to CLC, she also serves as a mentor to incoming student volunteers and as a senior board member with the SSDP. “You learn how to think strategically, come up with the theory of a case, and own your work around that.”

As a result of her clinic experiences, Dragonetti has settled on a clear career direction: to become a pulic defender or legal aid attorney. “Working with some of our most underserved neighbors here in Silicon Valley has inspired me to help improve acess to justice back home in the South,” she says. SL