Would You Really Like Hillary More if She Sounded Different?

How biases shape our perceptions of a powerful woman’s voice

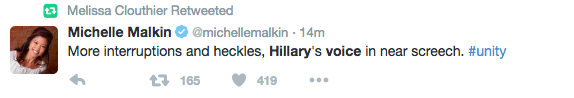

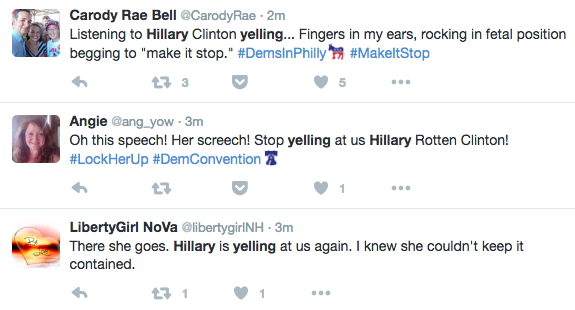

When Hillary Clinton made history by becoming the first female presidential candidate last week, she sounded enthusiastic. And people took note:

This is, of course, nothing new for “shrill-ary,” whose voice has been scrutinized ever since she was an aspiring Arkansas first lady with “a clipped Northern accent and hippy wardrobe,” according to the New York Times.

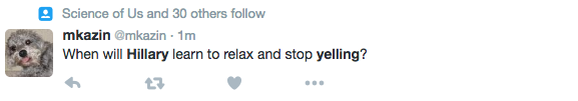

The criticism has only heated up as she’s become the most watched woman in America. In February, journalist Bob Woodward complained “she shouts, there’s something unrelaxed about the way she’s communicating.” Former RNC chair Michael Steele claimed she was “going up every octave with every word.”

Some women have decried the unsolicited voice lessons as sexist. Others have countered that there’s nothing discriminatory about critiquing a major presidential candidate.

Just because Clinton’s candidacy is historic, of course, doesn’t mean the media should go easy on her. At the same time, there’s a sense that Obama, the hip college professor, and George W., the West-Texas beer buddy, could speak a bit more freely. Their voices were heavily parodied, not pilloried.

With so many people channeling their inner Simon Cowell when it comes to Clinton’s vocal stylings, we set out to determine whether there’s any validity to the griping. After running analyses on Clinton’s speeches, several voice experts told us that, yes, there are things Clinton could improve about her delivery. And yes, there might still be sexism at play.

Let us unpack:

More like chill-ary

First, Clinton does not go “up an octave” with every word, according to Rosario Signorello, a linguist who examined the speeches of many major political leaders, including Clinton and Donald Trump, for a recent poster presentation. Instead, Clinton tends to lower her pitch over the course of speeches, perhaps in an attempt to seem more dominant. Trump is the one who rises as he goes, Signorello found—a good way to keep emotions swelling.

The mic effect

But several experts said Clinton does run into problems at the microphone occasionally. According to Amee Shah, an associate professor of health science at Stockton University, during rallies Clinton seems to breathe from her chest and neck, rather than her belly. That can make her sound too strained—and yes, loud—through a microphone, even when she sounds normal in smaller gatherings.

Likable enough?

Shah also noticed that Clinton has cleaned up her voice and accent over time, largely wiping away her Midwestern folksiness and Arkansas softness. Today, her clear, careful emphasis might actually be working against her: People like presidents whose voices have a little bit of character.

“A clean accent sounds too perfect,” Shah said. Members of the audience, with their drawls and twangs, can’t relate. “That is why despite the gruffness and harshness in Trump’s voice, many people still prefer his voice over Hillary,” Shah added.

Shah sent us this clip, of Clinton on the campaign trail with Bill in 1992, in which Shah said Clinton sounds more “natural.”

It evidently wasn’t natural enough for the people-on-the-street interviewed for the segment. One woman, with character galore, said, “We got no use fah ha.”

“She’s a very aggressive woman,” another man declared, “and she’s overly ambitious.”

That was just 24 years ago.

The perfectly average woman

When Shah watched several Clinton speeches in a row, she found something, well, unremarkable: Clinton’s voice is about average in pitch and loudness for a woman her age. Clinton could breathe differently, emphasize more interestingly, or perhaps change her accent again (it looks like Texan is up for grabs). But “even if it was an awesome change and she was the best speaker ever,” said Laura Verdun, a vocal coach in Washington, D.C., “there’s still bound to be criticism.”

Clinton is, after all, decidedly un-average in other ways.

As Clinton admitted during her convention speech Thursday, “some people don't know what to make of me.” People don’t tend to know what to make of powerful women in general.

Research has repeatedly shown that female leaders are judged more harshly for their errors than male leaders are, even when they’re doing the exact same job. That could explain why Bernie Sanders, who often sounded like an irritated aardvark, somehow managed to escape the decibel-scolds.

Studies also show that people are inclined to believe that “what is typical is good”—that what has always been should always be. It’s a subtle bias that works against women like Clinton. Typical women, who never shout, often smile, and never reach the highest public office in the land, are good. Typical politicians, who aren’t female, are also good. Americans have never heard “I accept your nomination” spoken by a woman, so Clinton is anything but typical.

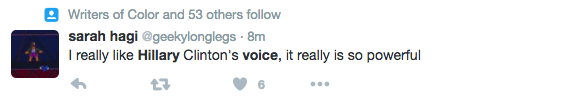

An optimist might hope Clinton’s candidacy will change what people think a pleasant woman’s voice sounds like:

What’s less clear is if Clinton will try to change her own voice in the meantime.

Periodically, we’ve see glimpses of her strong belief that women are not to be muzzled. In 1995, for example, she was still stinging from the defeat of her health-care plan when she went on a tour of South Asia. It was a bitter time. As the Times reported, Clinton told one young Pakistani girl that she no longer has any role models, and she quipped to another that Americans have some “rude nicknames” for her.

But amid the gloom was a moment of hope. At a stop at a research institute in India, Clinton read a poem written for her by Anasuya Sengupta, an Indian schoolgirl:

"Too many women in too many countries speak the same language—of silence …

When a woman gives her love, as most do, generously, it is accepted. When a woman shares her thoughts, as some women do, graciously, it is allowed.

When a woman fights for power, as all women would like to, quietly or loudly, it is questioned

And yet, there must be freedom, if we are to speak. And yes, there must be power, if we are to be heard.

And when we have both (freedom and power), let us not be misunderstood.”

Daniel Lombroso contributed reporting