Is Robert Alter the Jerome of the new millennium? I rather think he is, and I’m in good company. My friend, the poet and ctitic Adam Kirsch, has a review at the newest issue of the Jewish magazine, Tablet, and will pretty much convince the fence-sitters it is so: “Translating the entire Bible single-handed—a text of more than 3,000 pages, in this edition—is a scholarly and literary feat that puts Alter in the company of legendary figures such as Jerome, whose Latin translation of the Bible was adopted by the Catholic Church, and Martin Luther, whose German version helped to fuel the growth of Protestantism.”

The Alter Bible has been issued in installments since 1997, first Genesis and then The David Story. I lost track after that (but wrote about it here). Now is my chance to catch up.

An excerpt:

The Bible is a refractory book, never behaving quite as we expect it to. Indeed, much of the creativity of Jewish tradition has been devoted to harmonizing the actual Bible with Judaism’s changing expectations of what it should be. The rabbinic genre of midrash tries to make sense of the text’s many narrative contradictions and ethical perplexities. The Talmud assumes that every word in the Torah is there to teach a point of halacha, while Maimonides insisted that the Bible actually teaches the same truths as Greek philosophy, though it uses an allegorical method that can easily mislead the ignorant. And the mystical Zohar, written in medieval Spain, says that if all there were to the Torah were its surface meaning, it would be easy to write a better book: It is only the hidden, esoteric content of the Torah that makes it sacred.

The one thing the Bible could not be, for most Jews throughout history and many still today, is mere literature. After all, literature is a secular art, a product of the human imagination, while the Bible is supposed to be a sacred text, the product of divine inspiration. Perhaps the first person to openly suggest otherwise was Baruch Spinoza, the 17th-century Jewish philosopher, who daringly wrote that the books of the Bible ought to be studied in just the same way we would study Greek and Italian poetry.

Robert Alter’s newly completed English translation of the Hebrew Bible shows what it means to take the idea of the Bible as literature seriously. For Alter, the most important thing for a translator to know about the Bible is that its authors were great literary artists. This doesn’t mean that they lacked a religious purpose, of course; but it does mean that they paid close attention to literary technique, without which their writing might never have become canonical in the first place. Getting the Bible right, for Alter, means offering the English reader a literary and aesthetic experience that comes as close as possible to the Hebrew reader’s.

He also tackles a gripe I’ve had for some time, and insists, as I do, that it should be considered as an anthology and not a single book. I thought that would have been self-evident by now, but people are continually claiming that “the Bible says that.” What can I do, but grab them and shake them by the shoulders, shouting: “Which book? Who said it? And when was it written, by whom, and under what historical circumstances?”

Adam Kirsch again:

Another strength of Alter’s translation is the way it conveys the Bible’s internal diversity, and the tensions it can cause. Bible, in English, is a singular noun, and we refer to the Bible as “a” book. But the word comes from a Greek plural, biblia, and one of the traditional Jewish names for the Bible is “the twenty-four books.” This plurality gets lost when we think of the Bible as one big book, and implicitly expect from it some kind of stylistic and theological unity. This expectation is reinforced by the idea that all the parts of the Bible stem ultimately from the same author, God (even if Jewish tradition holds that different books were written by different people: The Book of Job by Moses, the Psalms by David.

Yet the Bible disappoints this expectation of unity at every turn. Written over a period of five or more centuries by dozens of different authors, it is best thought of as anthology rather than a book: verse and prose, myth and history, genealogical catalogues and territorial surveys, architectural measurements and erotic poetry. Even individual sections of the Bible are full of narrative inconsistencies and duplications that suggest they are combinations of several different texts. (Abraham goes to Egypt and pretends Sarah is his sister on two occasions; Noah is told to take two of each species of animal on board the ark, then in the next sentence to take seven of each.) Spinoza doubted that the true origins of the Bible could ever be discovered, but modern scholarship has gone a long way to proving him wrong, discerning different layers in the text that reflect various origins and agendas.

Read the whole thing here.

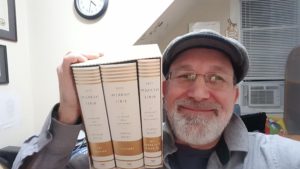

Now I will have to find a way of coughing up $75 for the three new volumes. My friend the rabbi, David Goodman of Philadelphia, already has, and my teeth grind in jealousy. “I couldn’t resist,” he confessed.

You thought I was pulling your leg with that headline, didn’t you? Below, Berkeley’s Robert Alter describes how the Bible is like Franz Kafka – and shares his beefs about other translations.

Tags: Adam Kirsch, David Goodman, Robert Alter

February 2nd, 2019 at 9:40 am

Robert Alter is a wonder, who has introduced us to the wonders of the Hebrew Bible as no one else in our generation. Chapeau! Bravo! Congratulations!

February 2nd, 2019 at 10:20 am

Good to hear from you, Marilyn! And I couldn’t agree more!

February 2nd, 2019 at 3:47 pm

Alter retains the original ambiguity and beautify of the ancient texts. But he also corrects and specifies some of the vague soaring rhetoric of the KJV. Apparently “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land” in the original literal Hebrew is closer to waive all debts.

February 2nd, 2019 at 4:56 pm

Somehow “waive all debts” is less inspiring. But yes, the KJV has James I stamped all over it.